With the release of Ben Wheatley’s brand new adaptation of Daphne du Maurier’s gothic romance novel, Rebecca, I wanted to look back at Hitchcock’s classic, to explore his relationship with Joan Fontaine, and how he shaped her image in the film, as he did with so many of his Hitchcock Heroines.

As his first American film, celebrating its 80th anniversary this year, it was a spectacular start to his legendary Hollywood career.

Rebecca features a timid and self-doubtful lead character, nameless throughout the book and films, who is married to an older, troubled man, and just like Jane Eyre, there’s a ghost-like character, a repressive mansion and a purging fire. Much as the 2020 Rebecca is reflective of the anxieties we have all felt in lockdown, Hitchcock’s film heralded a darker style of woman’s film at the advent of a new global conflict, with a character who is filled with insecurity and fearful of losing her love.

Rebecca was also a very important film for its star, Joan Fontaine, as it earned her an Oscar nomination; elevating her from the small, flighty roles in films like The Women. As Picturegoer in 1940 wrote, after the premiere of Rebecca, Hollywood discovered Joan Fontaine is a ‘great actress… Joan needed the right kind of role; then more than ever, she needed exactly the right kind of direction in that role.”[1]

Yet there was heavy competition for the role of the second Mrs De Winter. Hitchcock had hoped for Nova Pilbeam, the young star of his films Young and Innocent and The Man Who Knew Too Much. And when Laurence Olivier was cast at Max de Winter, the British actor campaigned for his lover Vivien Leigh to be cast opposite him. She even did some screen tests, but Hitchcock found that she was far too much like Scarlett O’Hara, having just come from the set of Gone with the Wind, and he noted that her tests did not hit the right note ‘as to sincerity or age or innocence.’[2] Even Selznick agreed, writing to her: ‘It is my personal feeling that she could never be right for the girl, but God knows it would solve a lot of problems.’ [3]

Hitchcock later commented that Vivien Leigh would have been perfect as the title character, Rebecca – as she was beautiful, confident and fiery.

As he had done with Gone with the Wind, Selznick chose to audition countless numbers of actresses, including Loretta Young, Anne Baxter and Maureen Sullivan. In July 1939 Hitchcock ran through the list of potentials, providing caustic and witty comments to Selznick on whether they were suitable, perhaps to make a dig at this talent search. ‘I think he really was trying to repeat the same publicity stunt he pulled in the search for Scarlett O’Hara,’ Hitchcock said. ‘He talked all the big stars in town into doing tests for Rebecca. I found it a little embarrassing, myself, testing women whom I knew in advance were unsuitable for the part.’ [4]

Hitchcock reviewed all the auditions with his wife Alma and assistant Joan Harrison, two women who he relied on for their opinions. In his comments, he noted that Jean Muir was ‘too big and sugary’; Miriam Patty was ‘too much Dresden china. She should play the part of the cupid that is broken – she’s so frail,’ and of Joan Fontaine, he wrote ‘possibility. But has to show fair amount of nervousness in order to get any effect.’[5]

Fontaine was a particular favourite for Selznick. At a dinner held by Charlie Chaplin in 1938 Joan Fontaine had been seated next to Selznick, and she had raved to him about Du Maurier’s just-released hit novel, that it would make a ‘fascinating, unusual movie,’ and coincidentally, Selznick revealed to her that he had just bought the movie rights.

She waited and waited for news on whether she had won the role, and it was while on honeymoon with her new husband Brian Aherne in Oregon that she eventually received the good news via telegram. Conflicted as to whether she wanted to give up acting to be the dutiful wife, she recalled in her memoirs that she was ‘stunned, I could only murmur that I wasn’t sure I still wanted a career.’ [6]

Hitchcock is known for paying great attention to how his actresses looked on screen, supervising their hair, their make-up and their costumes, in order to compliment his vision as a whole. Yet for Rebecca, it was Selznick who led on many of the costume decisions, designed to chart the growth of the second Mrs de Winter. Selznick noted that he wanted the girl ‘to look as pretty and appealing as she could as long she was not glamorous.’[7]

Costume was important to the narrative as the girl’s awkwardness and naivety is at first revealed in her unsophisticated skirts, blouses and cardigans. After her arrival at Mandalay she wishes to change into more glamorous gowns, like those of Rebecca, yet she lacks the confidence to pull it off and she is ultimately ridiculed by her husband.

Despite its importance, there was no screen credit for the costume design because Selznick drastically reduced the wardrobe budget to save money while battling budgets for Gone with the Wind. Ed Lambert from Western Costume Company was charged with sourcing suitable pieces from existing stock, and Selznick instructed him: ‘I don’t think we ought to have to build a single costume for this picture. The lead should be outfitted entirely from stock things purchased around town and the other costumes also ought to be stock. I feel that there is a possible saving of between $5000 and $7500 in Ladies’ Wardrobe.’ [8]

Some of the costumes in the film have been credited to Hollywood favourite Irene Lentz, yet it was unlikely the budget was stretched to the glamorous designer, as the idea of hiring costume supremo Travis Banton was dismissed by Selznick, because he charged $150 per gown. Although there were a number of publicity shots featuring Joan Fontaine in gowns that didn’t appear in the film, but which may have been Irene’s.[9]

The girl’s awkwardness is what attracts Max, and he tells her that he hopes she will never change from her cardigans and sweaters. He wants her to be young and innocent forever, even though she wishes ‘I was a woman of about thirty-six dressed in black satin with a string of pearls.’ Later, at Mandalay, she does wear a black dress with pearls, but it’s a little too big for her, indicating how she can’t quite get it right when she tries to hard.

Selznick thought her dresses in the opening scenes in Monte Carlo should have a low waistline, to make her look younger, and in a memo suggested to Ed Lambert that he ‘try some shop that carries clothes for extremely young girls which we can see along with the sketches which I understand you are preparing.”[10]

The 1930s trend for very severe, pencilled eyebrows was shifting by the end of the decade in favour of a more natural, unplucked brow, as championed by Ingrid Bergman. Selznick was very much aware of the shift, particularly as Bergman was his contract star, and he was horrified to see Fontaine with overly plucked eyebrows that didn’t suit the sweet girl she was playing. He scolded make-up artist Monty Westmore: ‘We don’t seem to have learned our lesson and we are still doing tricks with Miss Fontaine. In one of the most important close-ups in the picture, the one in today’s rushes where the character is almost driven to suicide, she has on eyelashes that compare with Miss Dietrich’s at her worst… what can I do to get you make-up men to throw away your kits and your tweezers? The public is so far ahead of you all and is so sick of your make-up that you are all managing to contribute to the destruction of stars.’[11]

The gown for the masquerade ball was also a major plot point. In sketching her costume for the ball, she at first considers a bold Joan of Arc warrior uniform. But following the suggestion by Mrs Danvers, she ultimately decides on a frilled, feminine dress based on the portrait of the wall. It should be non-threatening and in line with the luxurious-wear she has seen in Rebecca’s room, yet Danvers sets her up for a fall, with the frills and flounce seeming to add to her humiliation. While the dress in the portrait in 2020’s Rebecca is tight, scarlet and with a plunging neckline, Ed Lambert referred to the pages of the book when sourcing a suitable gown from stock. He noted the description of ‘the girl in white, with a hat in her hand…those puffed sleeves, the flounce, and the little bodice.’

When it came to creating the Mrs Danvers character, Hitchcock embellished the nature of her relationship with Rebecca to imply an obsessive attraction. In a wonderfully sinister scene, Judith Anderson, dressed stiffly as an Edwardian parlour maid, runs her hand over Rebecca’s belongings, stroking the furs and satins, and the luxury underwear made by ‘cloister nuns.’

‘Mrs Danvers was almost never seen walking and was rarely shown in motion,’ said Hitchcock. “If she entered a room in which the heroine was, what happened is that the girl suddenly heard a sound and there was the ever present Mrs Danvers, standing perfectly still by her side. In this way the whole situation was projected from the heroine’s point of view.’ [12]

While Fontaine’s costumes were mostly dowdy and unfashionable, the wardrobe for the late Rebecca was used in promotions to attract a female audience. Selznick’s assistant Katherine Brown negotiated a deal with fashion designer Kiviette and hat designer Robert Dudley to create a luxury Rebecca wardrobe, based on the myth of ‘Rebecca’, and which tied in with a poster showing a silhouette of a woman with the caption ‘the most glamorous woman of all time!’ As part of the promotion there were also plans for department store windows with mannequins in masks and with blue navy hair to ‘give the mannequins an unreal quality.’ [13]

Kiviette designed a midnight blue negligee and dressing gown embossed with the letter ‘R’, only be seen briefly hanging in the wardrobe and which Selznick specified to be ‘be exotic and very sophisticated, but…be careful they don’t look like Mae West.’[14] He liked the final result so much that he asked to keep it for his wife Irene’s ‘Christmas stocking.’[15]

While Selznick was very much in control of the style of the film, Hitchcock worked hard like Pygmalion to coach the inexperienced Joan Fontaine in her performance. On one occasion he slapped her, on her own request, in order to bring on the tears for a particularly emotional scene. She’d asked a number of actors on set to give her a slap so that she could feel the right emotion, but it was only Hitchcock who obliged.

There were continued concerns as to whether, in Selznick’s words, Joan was ‘capable of the big moments’. Hitchcock used a few psychological tricks to help her to forge the insecurity needed for the role, such as making her feel that the other cast members disliked her. She felt ignored by the weighty English actors, Olivier, Gladys Cooper, Judith Anderson, George Sanders, who she said were a ‘clique lot’, and felt that Hitchcock had used a ‘divide and conquer’ technique.

There was one story recounted when the director surprised Fontaine with a birthday party on set, but that her co-stars didn’t bother to come out of their dressing rooms for it, and Hitchcock didn’t summon them. While it is extremely unlikely Hitchcock would have had that much control over the other strong-minded cast, there was also resentment from Laurence Olivier that she won the role over Vivien Leigh. When Olivier was made aware that Fontaine was a young bride, and her new husband was Brian Aherne, he dismissively replied ‘Couldn’t you do better than that?’ This destroyed her belief in her husband, and she said that she couldn’t look at him the same. [16] Olivier’s ‘attitude helped me subconsciously,’ she said in her autobiography. ‘His resentment made me feel so dreadfully intimidated that I was believable in my portrayal.’[17]

Despite her experiences on set, after the film’s release, Joan Fontaine praised Hitchcock for being ‘marvelous. I can’t say enough for him. He was practically a Svengali to me. I could read his mind, know instantly what he wanted in a scene, just watching his face. Hitch has one of the most mobile faces in the world. Every reaction he wants from a character is unconsciously registered there.’ [18]

Rebecca was a smash hit on its release in 1940, winning Best Picture at the Academy Awards, and as the first American-made film in Hitchcock’s career, it cemented his position as one of Hollywood’s most important directors. But, as Hitchcock always said, it was really a David O Selznick picture. The producer was involved in all aspects of the story, driving its look and feel, and involving himself in all casting decisions and wardrobe decisions.

Joan Fontaine was directed by Hitchcock again, in 1941’s Suspicion, having written to Hitchcock pleading for him to cast her once more, and this time, she won the Best Actress Oscar, making her to the only actor in a Hitchcock film to win one.

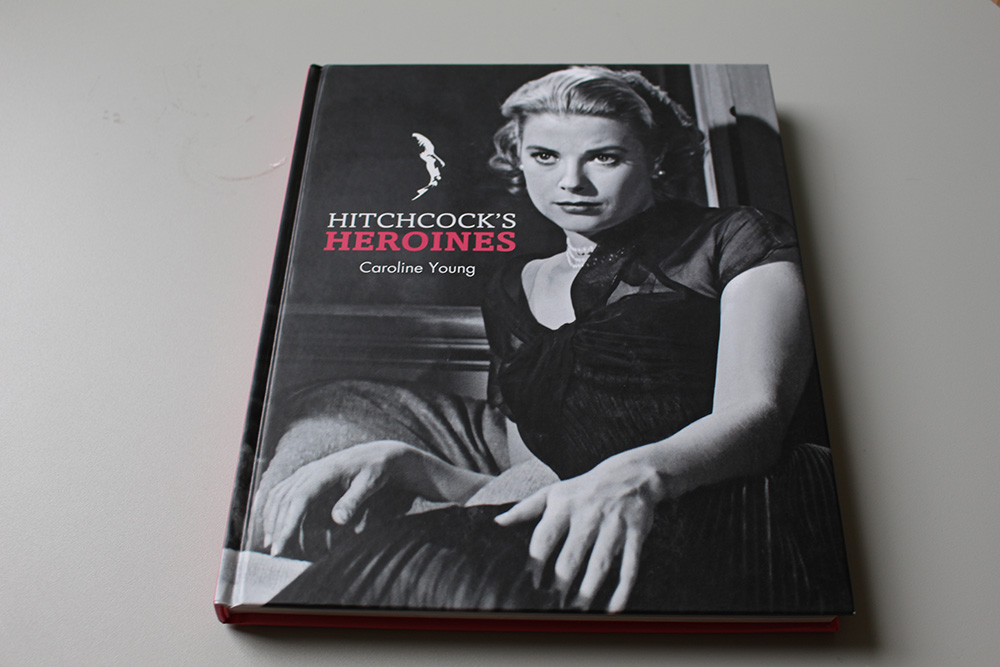

As adapted from my book Hitchcock’s Heroines, published by Insight Editions.

[1] Picturegoer, 21st September 1940, Miss Fontaine becomes an actress

[2] Behlmer, Rudy, Memo from David O Selznick, Macmillan, 1973, P271, August 18 1939, Mr John Hay Whitney

[3] Behlmer, Rudy, Memo from David O Selznick, Macmillan, 1973, P264

[4] Alfred Hitchcock: A Life in Darkness and Light, by Patrick Mcgilligan

[5] Rebecca, production file, Interoffice communication, Hitchcock to Selznick, 10 July 1939, Girl from ‘America’

[6] Joan Fontaine, No Bed of Roses, 1978, WH Allen, P109

[7] Behlmer, Rudy, Memo from David O Selznick, Macmillan P270, P281

[8] University of Texas, Harry Ransom center, David O Selznick Collection, Selznick to Mr Ginsberg, 25th July 1939, Rebecca budget

[9] University of Texas, Harry Ransom center, David O Selznick Collection Memo, Ed Lambert to Mr Klune, Mrs Rabwin, 7th September, 1939

[10] Harry Ransom center, David Selznick collection, Selznick to Ed Lambert, Miss Dabney, 30th September 1939

[11] Behlmer, Rudy, Memo from David O Selznick, Macmillan P270, October 9 1939, to Monty Westmore

[12] Truffaut, Francois, Hitchcock/Truffaut, Simon and Schuster, 1983, P129

[13] Harry Ransom center, David Selznick collection, Miss Kay Brown to David Selznick, 10th October 1939, Rebecca Luxury wardrobe

[14] University of Texas, Harry Ransom center, David O Selznick Collection Selznick to Kay Brown, 14th September 1939

[15] Harry Ransom center, David Selznick collection, Selznick to Kay Brown, 8th November 1939, Rebecca Luxury wardrobe

[16] Alfred Hitchcock: A Life in Darkness and Light, by Patrick Mcgilligan

[17] Alfred Hitchcock: A Life in Darkness and Light, by Patrick Mcgilligan

[18] Motion Picture magazine, August 1940, I don’t want to be a career girl! James Reid